EPDR is Not What I thought

EPDR and Stereophile

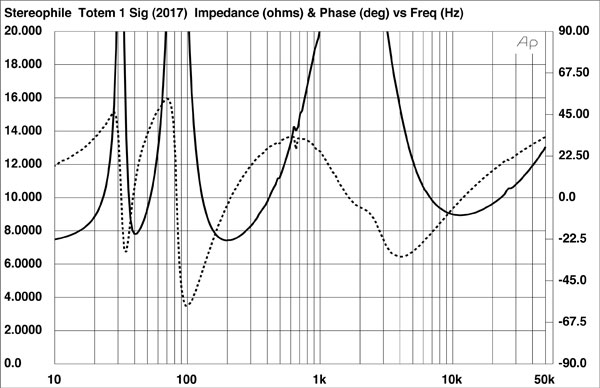

This blog post is opinion, history and math. I started out as a champion of EPDR until I learned exactly what it means and how it works. The understanding in the layman audio community is that EPDR is a better way to understand how an amp may sag under normal operating conditions, and therefore alter its output, but the truth is it isn’t doing what you think it is. For more information on how hard-to-drive has been defined in the past, turn to my blog post here. However after doing the research from the original EPDR articles and the source papers from Eric Benjamin I’m convinced EPDR is being oversold and overused among us. As you’ll read, this author is very skeptical of the value of EPDR vs. how much it is used in the community and how it is interpreted. Hopefully whether you agree with me or not this paper will give you clarity from which to make up your own mind.

Conceptual Invention

In 2007 Keith Howard coined the concept of Equivalent Peak Dissipation Resistance in his article Heavy Load: How Loudspeakers Torture Amplifiers. The idea of EPDR is to help readers understand more about a speaker and how hard it is to drive. Howard writes:

But for a magazine audience, the principal interest in a loudspeaker’s load impedance lies in gaining some indication of its compatibility with a given amplifier.

The rest of the article needs very careful reading, because to many readers it sounds like he’s saying this is a better impedance measurement, but he never actually proves that. He weaves together a lot of charts, and even contradictory data from Otala:

That was left to others to check, and their results suggest that [sigh of relief] this is not a phenomenon with any practical relevance. That is what Dolby Labs’ Eric Benjamin found when he investigated the issue in 1994 (footnote 3). It’s what I found, too, when I unwittingly reprised some of Benjamin’s work in 2005 (footnote 4), albeit using a software-analysis approach rather than an oscilloscope. While in this context you can’t prove a negative—there is always the possibility that some pieces of music will contain just the waveform necessary for a particular speaker to demonstrate the Otala effect—the available evidence suggests that this probably occurs extremely rarely, if at all.

but then Howard turns the ship around, after saying this isn’t important:

No, the problem with conventional impedance measurements lies not in the measurement method itself but the way in which its results are presented.

He then goes on to use Benjamin’s work with a lot of graphs, but this part is key: He labels the charts as showing equivalent dissipation, or rather how much heat will a typical linear amplifier produce. This is not a measure of how a speaker’s output will vary but how hot the amplifier will get. The “D” in EPDR stands for dissipation. This means heat at the transistor on the amplifier.

In personal correspondence between this author and Jack Oclee-Brown (JOB) (November 24, 2025) he gives the single useful feature of EPDR:

This is the usefulness of EPDR because it tells you if one speaker is more likely to trigger Safe Operating Area protection (to clip) than another.

As a speaker designer, transforming Benjamin’s formulas into relative resistance makes it agnostic of the amplifier’s rated output power, so for JOB I can definitely see how it is useful while evaluating crossover alternatives.

Despite this being useful for a speaker designer, I want to make this point clear: EPDR is not telling us the same information about how hard to drive a speaker is vs. the raw impedance curve, and it does not tell us how the speaker will sound wiht amp A vs. amp B. It is only about how much heat the amplifier’s output devices will generate when driving that speaker, and why it may clip early. Of course, an amplifier that clips will distort and sound terrible, but that’s a different set of problems than the audiophile and speaker measurement community thinks it is. Speaking for ourselves, we thought EDPR would do a better job of explaining why some speakers sound different with different amps, but after reading the source material we now understand that is not the case. Specifically, when an amplifier “sags” or underperforms. Typically a hard to drive speaker may sound like there’s a depression in the midbass with some amps, pushing a buyer to purchase an amp with more current capbility, but EPDR does not explain this phenomenon at all, it can’t.

That is, until clipping or overheating occurs, EPDR has nothing to do with the voltage or current at the speaker terminals. It does not demonstrate additional distortion, or reduced output. The invention of EPDR appears to be showmanship, aided by a lot of pretty charts in the article, and Howard letting the casual reader come to conclusions he doesn’t actually state.

Finally, it’s important to understand that EPDR applies ONLY to linear amplifiers. It has no relevance to Class D or switching amplifiers, which are becoming more common in high-power audio applications. The entire foundation of EPDR is based on the thermal dissipation characteristics of linear amplifier output stages. This is very different from the traditional impedance metrics which matter to all amplifiers and interacts with their output impedance the same way.

Howard’s article is where the conceptual confusion starts, but the equations themselves have their own messy publication history, which is worth understanding before we talk about the math.

Messy History of the EPDR Formulas

Because neither Howard nor Stereophile ever published a formal derivation, the history of the formulas and an understanding of who is using which version come to us through a patchwork of message boards, private communication and reverse engineering. Jack Oclee-Brown (JOB) was nice enough to put together the timeline as he remembers it in a private message. I share the contents here with his permission:

- 2007: Keith Howard comes up with EPDR and writes the Stereophile article. He derives Equation 1 but it’s not published. EPDR isn’t used by anyone for many years.

- 2014: I [JOB] wanted to calculate EPDR and so I did my derivation and contacted Keith to confirm it matches his. It does in email correspondence. I didn’t publish, it’s not my invention and I just wanted to use it at KEF.

- 2020 March: [Room EQ Wizard] adds EPDR calculation. JohnPM (author of REW) confirms Equation 1 is used but given the timing he can’t have used my pdf because it wasn’t public at this point

- 2020 Aug: Stereophile start adding EPDR calculations to their reviews. There’s some interest on ASR about how to do the calc and I post my derivation just to be helpful.

- 2021: VituixCAD adds EPDR.

- 2025: user cjlan01 on www.diyaudio.com noticed that there’s a discrepancy between Stereophile’s published data and Equation 1 so contacts John Atkinson and finds out they’re using [the simplified version] instead. Why they did this I have no idea but Keith is not a regular writer for Stereophile and it sounds like Jim Austin came up with [the Excel] equation.

My guess is that VituixCAD uses Equation 1, it’s only Stereophile who are calculating it incorrectly I think.

Notes: I have slightly edited the exchange above for clarity and used “simplified version” to describe the Stereophile / Excel formula, below as well as added links where convenient for the reader. Also, I’ve confirmed that VituixCAD’s numbers are very close to the Howard formula, and also a little optimistic compared to the Stereophile / Excel formula.

The Formulas

With that timeline in mind, we can look at the two equations that are actually in use today: the simplified Stereophile/Excel form and the more exact Howard version.

EPDR for Stereophile / Excel

In a separate message JOB wrote to us and says:

Stereophile use Excel to calculate EPDR and use a simplified version of the formula I derived (I guess they thought that was “good enough” and certainly much easier to type into Excel).

If this is true then from cjlan01’s message the Stereophile formula is:

\[ V_{diss} = 1 + 4.2 * |\phi|/90 \] \[ EPDR = Z_{mag} / V_{diss} \] To be clear, this is a linear approximation, but Howard provides a precise answer.

EPDR by Howard

Again, we have no knowledge of Howard explicitly taking credit for any EPDR formula via an academic paper or web blog. What we believe Howard’s formula is comes to us from JOB. JOB reached out to Howard and published in his notes in a post at Audio Science Review. Looking at JOB’s PDF, Howard’s formula (Equation 1 as described in the exchange, above) slightly simplified is as follows:

\[ \text{EPDR} = \frac{|Z|}{4\, \bigl( 1 - \sin\!\left( \tfrac{5\pi}{6} + \tfrac{2}{3}|\phi| \right) \bigr) \sin\!\left( \tfrac{5\pi}{6} - \tfrac{1}{3}|\phi| \right) } \]

We’ve covered the history of the conceptual invention of EPDR and the two formulas we are aware of. This has prepared us to discuss the underlying theory from Eric Benjamin.

Eric Benjamin’s Foundation

The underlying principle of EPDR, as Howard notes, is a paper by Eric Benjamin: “Audio Power Amplifiers for Loudspeaker Loads,” JAES, Vol.42 No.9, September 1994. The paper is copyrighted and paywalled, but fortunately formulas cannot be copyrighted, so we can walk through Benjamin’s ideas. Benjamin doesn’t directly publish a formula for EPDR. That’s not actually his goal. Benjamin’s paper is about power dissipation across devices in Class B amplifiers. In other words, he wants to know how much a transistor will heat up by calculating the Watts dissipated based on the load impedance.

Safe Operating Area

The safe operating area (SOA) for a transistor has instant and average components. Exceeding the peak power for microseconds (Formula 4) can destroy a transistor, as can exceeding the average power (Formulas 6 and 7) for extended periods of time.

The point that I want my readers to understand is that Benjamin’s goal, and formulas are to calculate power dissipation in the output devices of an amplifier. He is not trying to create a new impedance measurement for speakers, and is definitely not saying “the speaker will sound different because of this.” If anything, this is about heat sinks, and cooling. Even if you barely understand formulas, the term on the left of all three formulas is \(P_{d}\), power across a device, meaning a transistor. Power across a device is power that must be dissipated or let off as heat.

Instant Power Dissipation

I don’t want to make light of Benjamin’s work, but the three Benjamin formulas (4, 6, 7) involved which Howard probably uses as a foundation would be relatively simple for an electrical engineer to derive. The real value of Benjamin’s paper is in forcing EEs to think outside of the box when designing the thermal/power envelope of linear amplifiers. We’ll start with the instantaneous device dissipation formula (4):

\[ P_{d}(\theta) = (V_{s} - V_{0} \sin \theta)\left(\frac{V_{0}}{|Z_{l}|} \sin(\theta + \phi) \right) \]

Where \(V_{s}\) is the supply voltage, \(V_{0}\) is the output voltage amplitude, \(Z_{l}\) is the load impedance, \(\phi\) is the load phase angle, and \(\theta\) is the instantaneous angle of the output waveform. It is this instantaneous value which appears to be the source for Howard’s formula.

Learning Exercise for Equivalent Resistance

This is not part of EPDR itself, but a simplified teaching example to help readers visualize how dissipation-based equivalence works. We want to illustrate the concept of an equivalent resistance without the calculus Howard and JOB went through. We call this Equivalent Average Dissipation Resistance. The idea here is to give the reader with basic circuit theory a conceptual leg to stand on.

Let’s be clear of the concept and goal. We want to know the value for a resistor that would dissipate the same average power as the complex load. In other words, what value of \(R_{eq}\) would dissipate the same power as our complex load \(Z_{l}\) with phase angle \(\phi\) ? For instance, if we had a complex load of 4 Ohms at -45 degrees, what value of resistor would dissipate the same average power as that load when driven by the same voltage source? The resistor by definition would have a phase angle of 0, and therefore must be lower than 4 Ohms.

The calculation requires a two-step process. First we calculate a token voltage which will yield a token value for power dissipated given the load, and phase angle. Given power and voltage we then calculate the resistance. I say token because for our case, we don’t actually care about actual device power (\(P_{d}\)), we care about what would be equivalent resistance. So whether we calculate in the range of 0 to 1 watt, or thousands of watts, it doesn’t matter because we’re not actually sizing heat sinks.

Average Power Dissipation

Benjamin integrates his instantaneous formula (4, above) over the input signal’s conduction angle to get average power dissipation (formula 6 and 7, below). The end results are two formulas for power dissipation based on phase angle of the load, one for phase angles less than 50 degrees (6), and one for phase angles greater than 50 degrees (7).

Formula 6 if \(|\phi| \leq 50^\circ\) then:

\[ P_{d} = \frac{2 V_{ss}^{2}}{\pi^{2} |Z| \cos\phi} \]

Formula 7 if \(|\phi| > 50^\circ\) then:

\[ P_{d} = \frac{V_{ss}^{2}}{2|Z_{mag}|} * \left(\frac{4}{\pi} - \cos(\phi) \right) \]

Equivalent Resistance for Average Power

Then we set this equal to the power dissipated by a resistive load:

\[ \text{EADR} = \frac{2V^{2}}{\pi^{2} * P_{d}} \]

For our use, the exact value for V doesn’t matter. Set it to 10 or any other positive constant for all your calculations. Below is the R code which expresses Benjamin’s two formulas and our own EPDR calculator. Hopefully they will help you translate to your language of choice or even a spreadsheet.

# Benjamin's device dissipation formula.

# This is written for easier use with vectors in R

dev_power <- function (Zmag, phase_deg, V=10) {

phi <- abs(phase_deg) * pi / 180

# Go ahead and calculate both formulas, 6 and 7

P6 <- (2 * V^2) / (pi^2 * Zmag * cos(phi))

P7 <- (V^2 / (2*Zmag)) * ((4/pi) - cos(phi))

# Return either P6 or P7 based on phase angle

ifelse(abs(phase_deg) < 50, P6, P7)

}

# Calculate EADR

eadr_from_dev_power <- function(Zmag, phase_deg, V=10) {

# Calculate some sample power dissipation

P <- dev_power(Zmag, phase_deg)

# Now we calculate what resistor would give the equivalent as returned, above

EADR <- 2 * V^2 / (pi^2 * P)

return(EADR)

}We hope this exercise has helped you understand the concept of equivalent resistance in this context, though we have no idea if anyone will ever use this in real life.

Conclusion

We’ve walked through the publicly available sources (and sometimes not so public) for how Equivalent Peak Dissipation Resistance came into existence. We’ve shown the original research was intended to help amplifier designers understand how much heat their output devices would generate when driving complex speaker loads. We’ve discussed how Howard’s article puts EPDR adjacent to impedance and phase angle charts, but never actually proves that EPDR is a better way to understand amplifier/speaker matching in terms of sound quality.

While we have shown why we believe Stereophile and Howard’s formulas differ, we have no evidence that any version of EPDR is a better way to examine amplifier/speaker matching than the old impedance and phase angle charts. None of the derivations or formulas have anything to do with how a speaker sounds, or how well an amplifier can drive a speaker. As far as we can tell EPDR and the formulas from which it is derived have nothing to do with voltage or current across a speaker input. At the very best, EPDR can help understand which speaker is more likely to cause an amplifier to enter protective shutdown due to activation of SOA circuits, if any.

In addition, if we were designing amplifiers I would want to know the power output (Benjamin formulas 4, 6 and 7) directly instead of an equivalent resistance, which is why the entire concept of equivalent resistance in this field seems of limited use.

To paraphrase JOB’s point: EPDR may give a speaker designer some idea of the kind of amplifier needed to drive a speaker at full output. Below that, at moderate listening levels and power outputs EPDR doesn’t really give a consumer very much.