Speaker impedance is a complicated subject, but it is well known that some speakers are harder to drive than others. Sometimes there is a legitimate reason for this and sometimes a difficult impedance curve appears to be a marketing gimmick. We'll cover the basics of impedance curves, but what I want you to keep in mind is that a decent crossover designer CAN make an impedance much worse than it should be. A bad crossover designer can achieve the same.

I want to emphasize, that in some cases you can make the speaker much harder to drive, without changing the speaker's frequency response with an ideal voltage source. By doing so you have artificially created a speaker that is "highly discerning" of amplifiers specifically because amplifiers are not ideal voltage sources. They have limits based on the size of the power supply and output stage capacity, as well as use of feedback.

No two speaker models have the same impedance curve, the lower the impedance, and wider the "phase angle" the harder they are to drive. Phase angle means whether the voltage leads (inductive) or lags (capacitive) the voltage across a device.

A "hard to drive" speaker requires an amplifier with more current, and these amplifiers are usually more expensive than you would need for an "easy load."

The Physics

An impedance curve is a measure of the impedance of a loudspeaker at a variety of frequencies. In the worst case this curve will interact with the amplifier, causing the output frequency response to "track" or mimic the impedance curve. Where the impedance is high, the output is high, where it's low the output is low. The published frequency response measurements in Stereophile are always conditional on the amplifier being well in it's comfort zone.

This is essentially the common limiting factor of tube amps (yeah, not ALL tube amps) and why

some speaker makers like Fritz go out of their way to produce speakers which are easy to drive across their entire range.

The Gimmick

Many audiophiles unfortunately believe that a speaker that shows the difference between upstream components is more musical or easy to listen to. They are not. They just show differences better, but these buyers will prefer the speaker that is harder to drive, and then buy a bigger amplifier.

The way this gimmick works is that a buyer, hopefully a well-heeled audiophile, is tricked into buying speaker A instead of B because they believe it to be more "discerning." When you use a $1,000 amp and then swap it for a $30,000, 200 lb gorilla of an amp the speaker suddenly comes alive. Clearly, this speaker can hear all the great improvements between the first amp and the second, and therefore, the "discerning" speaker is going to reveal more about the music than any other. This also justifies buying monoblock amplifiers when you'd otherwise be happy with a small integrated had you picked an easier to drive speaker.

A speaker that is hard to drive causes a softening of output where the impedance is low. For instance, with an ESL tube amps often sound dull, and lacking treble. Swap to a nice solid-state and they bloom. Even a speaker with a mid-bass around 3 Ohms that is otherwise clean may make current delivery audible.

To be clear, there is absolutely no proof that a "discerning" speaker is actually better at playing real music, so this false logic is part of the whole inference chain.

Just like with romantic partners, a high-maintenance partner is just a high-maintenance partner, that doesn't make them smarter, funnier or more responsible at picking up the kids every day.

The Bad

Some speakers are by the nature of their physics never going to be an easy load. Two quick examples are electrostatics like Sanders or Martin Logan or the legendary Apogee Scintilla. Electrostatic panels are essentially constructed like giant capacitors, so a 1/3 Ohm at the high frequency is not uncommon.

The Apogee Scintilla, for instance, was essentially, a giant fuse, with a typical impedance around 1.4 Ohm as a result, and these speakers made Krell's amplifiers famous as they were some of the only amps capable of driving them. A 50 Watt/channel Class A amplifier would deliver 400 Watts into each of them at 1 Ohm. Fortunately later models were more reasonable around 3 Ohms.

Sometimes designers do pull more current for more volume, but these are still typically well managed by most amps. For instance, using 3 woofers in a single loudspeaker can lower the impedance. Also, we often can pick 4 or 8 Ohm woofers and may pick to get better matching to a mid or tweeter. The 4 Ohm version will play 3 dB louder thanks to the current doubling.

The Ugly

There are three loudspeakers I want to show you as example of really questionable impedance curves. To be clear, without taking a speaker apart it is impossible to know for sure what is going on under the hood, or whether this is an intentional "juicing" of the curve or a natural by product of good crossover design.

The speakers are:

Ages ago I did a complete electrical tear down of the Focals. What I found really disappointed me at the time. I found a bank of resistors and caps which appeared to be there deliberately to lower the impedance. Before we dive in lets look at a typical ported speaker impedance curve.

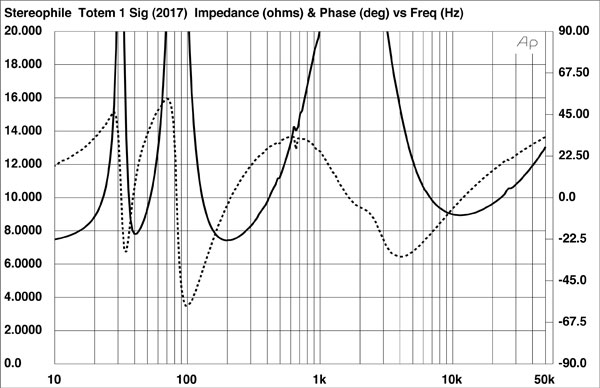

Here's an example of my own, the SNR-1, but almost ANY speaker in Stereophile with a port will be similar:

On the left are the typical dual impedance humps. On the right is the impedance hump caused by the midwoofer to tweeter crossover. The dual port and driver humps are expected and completely benign except for the weakest of amps.

Now that we know that, lets examine the speakers in order. First the Focal Profile 918. I actually simulated an alternate crossover for this speaker.

The green curve is the original. The second port resonance has almost vanished, and impedance remains under 4 Ohms from 40 to 400 Hz. At 95 Hz the impedance is about 2.3 Ohms. A punishing impedance for many amps, and also completely unnecessary.

The blue line is the simulated crossover improvement. The second hump is restored with much better impedance below about 150 Hz. For our three sample speakers this is the only one I have a schematic for.

Notice the capacitor and resistor banks? Completely unnecessary. You greatly improve the impedance just by removing C2, and with an inductor change can remove the second bank of resistors. These resistors are basically just here to steal power and heat up the interior of the speaker cabinet. Good thing it has a big port on the bottom!

Now that we have at least one good example of how impedance curves can be juiced or altered by a crossover designer I want to turn to a modern and not so modern example which might have similar issues.

KEF Reference 1 Meta

Important Update: Since publishing this paper

I've done a deep dive into the source and meaning of EPDR. I no longer think it carries as much weight as it should for determining hard to drive speakers. The missing hump information, and how it matches what the Focal Profiles does is still valid. It may turn out that the 1 Ohm EPDR for the KEF speakers is no longer truly valid or important.

The second speaker to cross my radar for possibly being deliberately demanding is the KEF Reference 1 Meta.

This bookshelf speaker was released sometime around 2022 and we benefit greatly by a full write up from Erin's Audio Corner. While Erin does note this is a very difficult to drive speaker due to a very low Equivalent Peak Dissipation Resistance (EPDR) of around 1 Ohm neither he nor any other widely published reviewer (which I'm not) mentions how odd the impedance curve is for a ported speaker.

Notice that like the Focal, the expected second hump is missing. We could ask "isn't this just an impedance flattening circuit? " Well, if it is then the fix is worse than the problem.

Revel Salon Ultima 2

While the Focal and KEF have been on the back of my mind for a while, it was over at DIY audio that the Revel and an important anecdote crossed my vision. User cyclotronguy asserts:

According to the Harmon engineers, they had specifically designed a

loudspeaker that while it looked easy to drive on-paper , in fact was

quite reactive and demanding so as to showcase the high wattage ML amps

they were about to market.

And it was that story, along with the impedance curve where it all clicked:

A very similar signature as the KEF. Missing second hump, and hard to drive.

Conclusion

I can't prove intention in any of these designs. It is not wrong to say that these speakers are all going to be "discerning" of amplifiers because anything other than top level amps will wither under the stress.

I can say that I don't know of a normal way the Focal speaker designers get to that schematic, or the KEF or Revel speakers end up missing a driver resonance hump. My advice to any audiophile reading this though is to please, consider if you really want a "discerning" speaker, or one that's easy to live with. It is my conclusion that in most cases you are going to enjoy more music more clearly and for less total cost of ownership with a less demanding speaker of the same type.

I'm definitely not saying you should not by an ESL. If that's what you want, go get it. I'm saying if you are deciding between a pair of dynamic speakers, please don't be tricked by this gimmick.